|

My

copy of Richard Weaver's The Ethics of Rhetoric is the first

edition published by Henry Regnery in 1953. The copy is not pristine,

as some book collectors would like. One previous owner graced every

page, student-wise, with abundant, dutiful underlining. The reader left

the margins clear, though—except for a couple of spots. One happens

to date the reading as 1966. The other is more interesting.

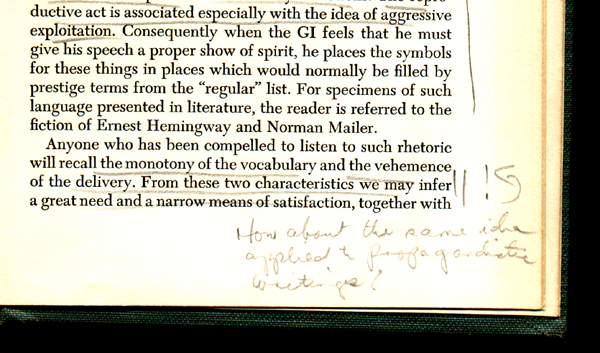

Weaver's last chapter, "Ultimate Terms in Contemporary

Rhetoric,"is very forceful, even caustic. Joining other rhetoricians

and semanticists who were instructed by the Second World War, he condemns

the ways those in power manipulate the public through language. He analyzes

"god terms" and "devil terms" (one of his god terms,

technical-writing teachers might be surprised to note, is "efficiency").

Toward the end of the chapter (page 225), he draws some examples from

U. S. military language or what he calls, borrowing a phrase from Kenneth

Burke, "the image of killing." He notes how some of the imagery

is identified with "faeces and the act of defecation," as

in the military/government term "elimination," and how "the

reproductive act is associated especially with the idea of aggressive

exploitation." He asks the reader to recall "the monotony

of the vocabulary and the vehemence of the delivery" characteristic

of the speech of GIs. At this point my reader can't hold silent any

more. Two vertical lines are slashed in the right-hand margin, and then

an exclamation point, and below is written, "How about the same

idea applied to propagandistic writings?" The reader rebels! I

wonder if this one remembered the outburst seven pages later on

reading Weaver's concluding words to the chapter: "It is worth

considering whether the real civil disobedience must not begin with

our language."

What

I find worth considering is why composition and rhetorical studies

show a near absence of interest in marginalia. Literary scholars,

of course, have thoroughly analyzed and faithfully reproduced the marginalia

of famous writers—Edward de Vere, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Katherine

Anne Porter, a hundred others (for a delightful read on the topic, try

H. J. Jackson's Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books, Yale

University Press, 2001). But the dynamics of ordinary readers as they

scribble in margins and between lines has never been studied. No doubt

the typical reader's marginal repartee lacks the punch of William Blake

verbal uppercuts ("Thus Fools quote Shakespeare," "Surely

the Man who wrote this never talkd to any but Coxcombs"). But discourse

analysis could still find plenty to analyze. Consider just the graphic

effects of the above gloss: the angry vertical slashes, the accusatory

arrow, the exclamation-point emoticon. . . .

In

Ex Libris: Confessions of a Common Reader (1998), one

of my favorite books about bibliomania, Anne Fadiman divides collectors

into two sorts, the "courtly lovers of books," who maintain

their volumes in pristine condition, and the "carnal lovers of

books," who underline and circle, jot in the margins and end-pages,

dog-ear pages to mark favorite passages, in short, talk back. I'm of

the second sort, and feel my first edition of The Ethics of Rhetoric

all the more valuable for the traces one previous owner left of a momentary

encounter 38 years ago when the normal etiquette of silence between

author and reader collapsed.

RH,

June 2004

|